The Role of Gluteus Maximus & Injury Prevention

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 28 Dec, 2023

- •

Significance, Postural Control, Related Pathology & Treatment

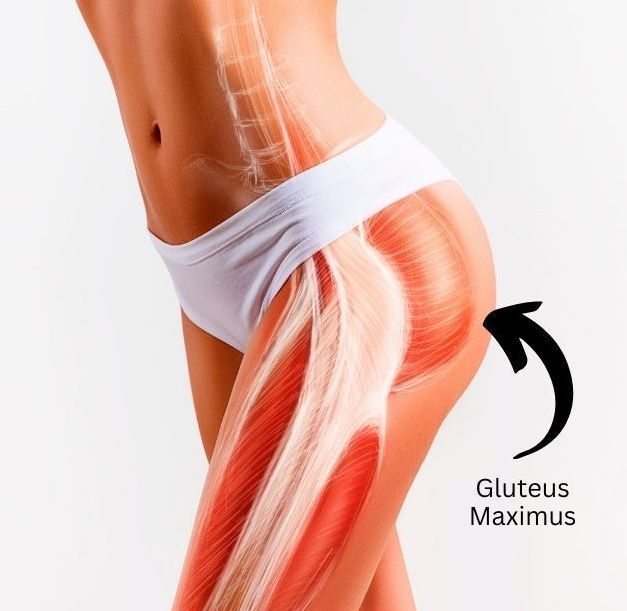

The Gluteus Maximus

Colloquially known as the 'glute max', the gluteus maximus (GM) muscle is the largest and strongest muscle in the human body (3). It is also the most superficial of the three gluteal muscles. The GM is prone to weakness and inhibition which has been known for the cause of numerous injury types in chronic pain (3). Knowing how to use this powerful muscle to its optimum can help prevent the occurrence of lower back pain and multiple injuries.

Functions of the GM muscle are extension and external rotation of the thigh at the hip joint, it is a chief antigravity muscle that helps keep the trunk of the body in an erect posture. Proper activation of the GM during daily activity such as walking and stair climbing can greatly reduce forces acting on the knee joints (5).

After researching around the topic of Gluteus Maximus atrophy, 'dead butt syndrome (DBS)' and 'gluteal amnesia' popped up in the search. Thankfully, a useful source by Gharib (2020) highlighted how there are no reliable articles or credible medical sources available on these so called 'conditions'. They concluded that 'DBS' does not exist, it is neither a true medical diagnosis nor medical concern (6).

However, what is evident is the possibility that an individual may have a reduced sensation upon contraction of the GM, have some difficulty maximally contracting the glutes or produce gluteal atrophy (6).

The GM acts as a stabiliser during movement during trunk rotation and stabilises the pelvis during single leg stance. It reduces adduction and internal rotation of the femur and helps prevent the trunk to forward lean during movement (3).

Should a New Year’s Resolution be made this 2024 year, it might be to strengthen and focus on optimising the use of one's Gluteus Maximus!

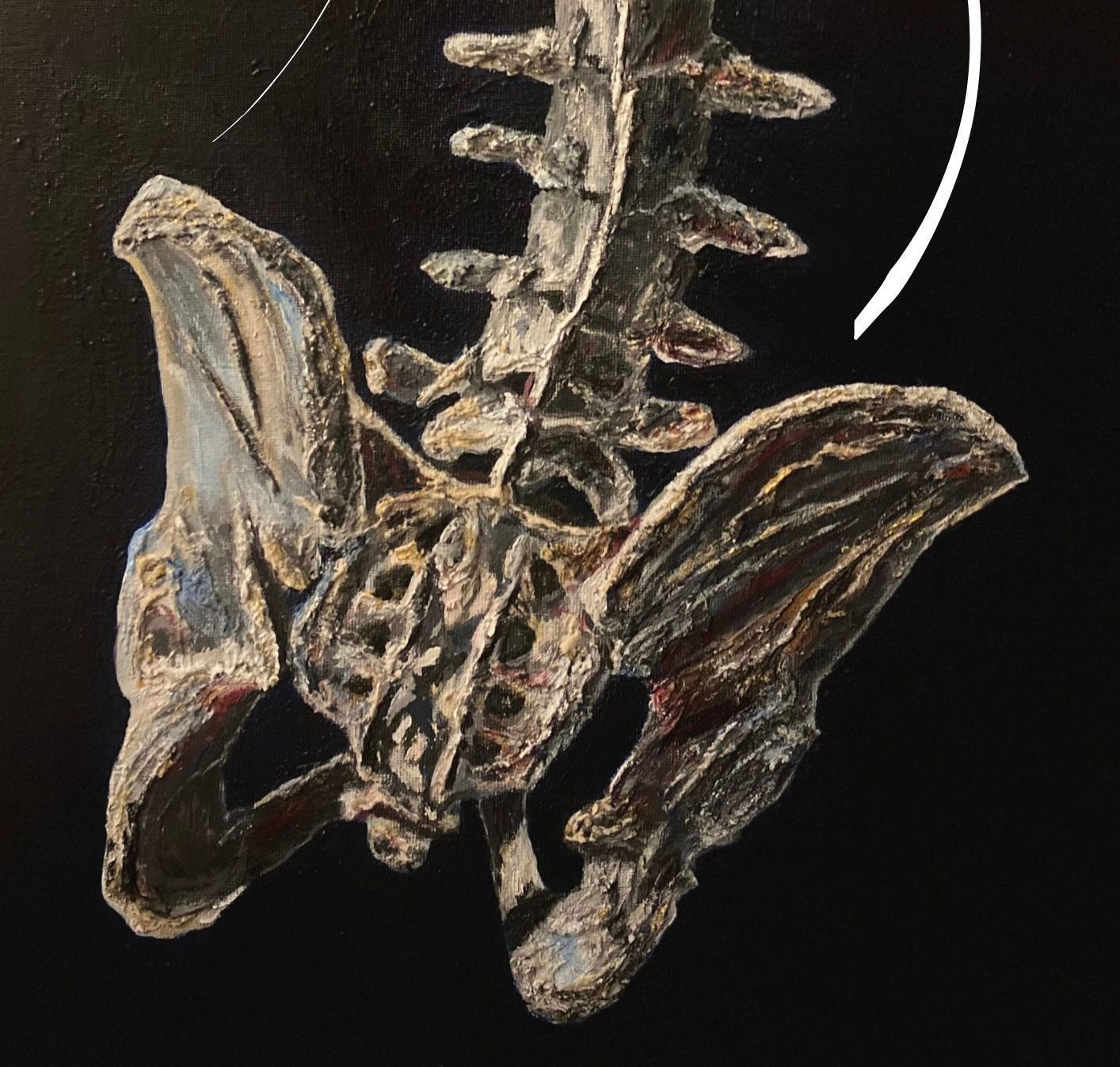

Anatomy

The GM originates from the posterior sacrum and coccyx, the posterior gluteal line of the ilium and inserts on the iliotibial tract and gluteal tuberosity of the femur. The GM is a powerful extensor and external rotator of the hip and the superior part of the GM acts as a hip abductor as muscle fibers in the GM are directed downward and outward (8).

Hip extensors, especially the GM, are important for many functional activities of daily living such as moving from sitting to standing, climbing stairs, and maintaining an upright posture during walking (8). Because the direction of the GM muscle fibers, especially deep sacral fibers of the GM, are perpendicular to the sacroiliac (SI) joint, GM contraction improves SI joint stability and plays a part in force transmission from the lower extremity to the pelvis during ambulation (8).

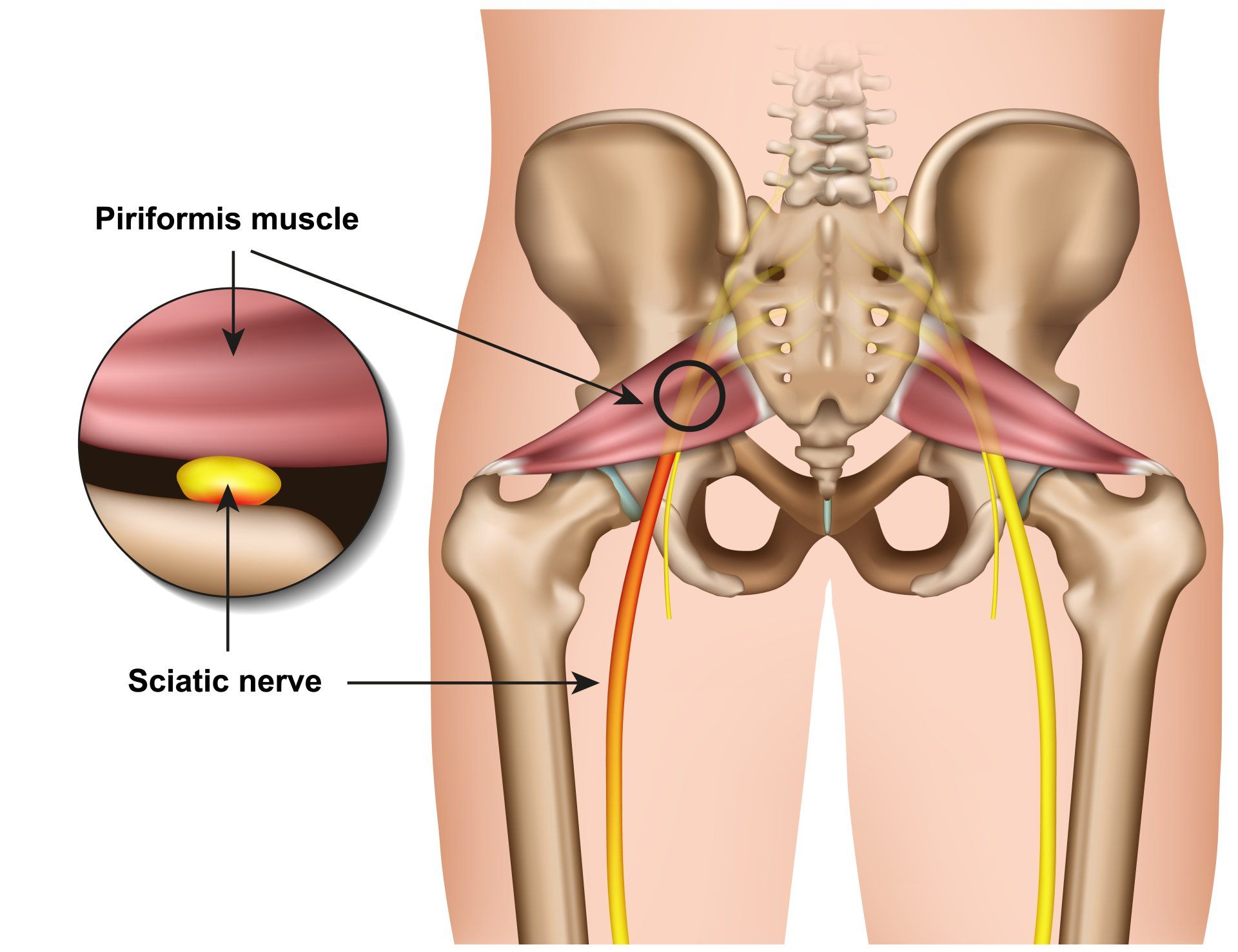

The sciatic nerve enters the gluteal region, more specifically it passes below (or occasionally through) the piriformis muscle in the form of ‘flattened band’. The sciatic nerve then passes ‘deep’ to the gluteus maximus, but does not supply any structures within the gluteal region before entering the posterior compartment of the thigh and travels down between adductor magnus and biceps femoris. The sciatic nerve splits into the common peroneal nerve and tibial nerves within the popliteal fossa at the back of the knee (8).

Pathology From Glute Maximus Inactivity

Weakness of the Gluteus Maximus has been implicated in numerous injury types such as patella femoral pain syndrome (PFPS) or anterior knee pain, anterior cruciate ligament injuries (ACL), lower back pain, hamstring strains, hip (femoral acetabular) impingement syndrome and ankle sprains (3). GM muscle weakness or dysfunction may be a contributing risk factor to or the result of injury (3).

Causes for GM Dysfunction - Lifestyle

Lifestyle factors significantly contributes to the reduced activity of the GM. Prolonged sitting causes the GM to be frequently weakened and lengthened increasing the risk of lower back pain (LBP) and sacroiliac (SI) joint instability and dysfunction. The body compensates by tightening the hamstring (HAM) muscles all because of the weakening of the GM. An excessive anterior pelvic tilt, lumbar lordosis with dominant erector spinae (ES), and lumbar rotation occur in place of a weak GM or delayed GM activation during hip extension (4).

Overtime the GM will atrophy and weaken causing the body to rely on the secondary hip extensor muscles such as hamstrings and hip adductors to produce hip extension torque clinically referred to as 'synergistic dominance' (3).

Altered Posture

An altered posture of the pelvis can influence the length-tension relationship of the GM. Quite often an anteriorised pelvic tilt is created during stance and gait which can cause hip flexors to tighten and local core weakness further elongating the GM (Buckthorpe, 2019).

The Glute Max and Patella Femoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS)

According to a systematic review by Barton et al., (2012), delayed and shortened duration of gluteaus maximus muscle activity may exist in individuals with PFPS, which can cause swelling and pain at the front or medial knee joint. They also found that there is moderate to strong evidence that gluteus medius muscle activity is delayed and of shorter duration during stair ascent and descent in individuals with PFPS.

It is worth noting that Gharib (2020) concluded that delayed ‘activation’ of the gluteal muscles is not necessarily exclusive to cause individuals lower back pain.

The Sacroiliac Joint

Weakness of the gluteus maximus can be related to abnormal loading of the SI joint and cause impairments associated with SI joint dysfunction. Anatomical studies suggest that the gluteus maximus can contribute to stabilising the SI joint with muscle fibers being perpendicular to the joint surfaces. Activation of the gluteus maximus was found to increase compressive forces across the SI joint (1). A study by Aurelio et al. (2018) found that subjects with persistent pain in the lumbopelvic region and whose clinical tests were positive for SI joint dysfunction demonstrated gluteus maximus weakness.

Men and Women and The Glute Max

A study by Vannatta and Kernozek (2021) found that males and females demonstrate differences in gluteal muscle forces and hip kinetics (motion) whilst running. Males produced greater peak gluteus maximus forces, but less gluteus medius, minimus, and hamstring forces than females during running. They also found that males demonstrated less hip adduction and greater hip flexion and anterior pelvic tilt than females. Meanwhile, healthy females demonstrate greater hip internal rotation and adduction motion whilst running. Females with ITBS demonstrated greater hip external rotation.

Females may have to generate greater gluteal medius and minimus muscle forces to meet the requirements imposed by their anatomy of having greater femoral adduction with relation to the positioning of the hip joint (10). This implies that females may utilise a different muscular strategy to generate hip extension and external rotation of the femur than males (10).

It was found that females produced a similar hip extension moment as males despite a reduction in peak gluteus maximus force whilst running. Thus, females may utilise a preferred pattern of hamstring force for hip extension rather than use muscular forces generated from the gluteus maximus (10).

PFPS - Single Leg Squat

Nakagawa (2019) found that males and females with PFPS showed increased ipsilateral trunk lean, contralateral pelvic drop, hip adduction, and knee abduction during a single-leg squat. These altered kinematics (or active motion techniques) were accompanied by reduced strength of the hip abductors and external rotators i.e. gluteal muscle. Additionally, in contrast to males, females with PFPS showed increased hip internal rotation and reduced gluteus medius activation during a single-leg squat (9).

Strength & Resistant Exercises

There is preliminary evidence that skill training and helping individuals understand better biomechanics during movement i.e. during gait/walking and running, as opposed to strength training, improves activation of the gluteus maximus and leads to the development of a biomechanics strategy to reduce loading of the knee joint (5).

Bridging exercises are the most commonly used by people with weak hip extensors and trunk muscles in physical therapy programs.

However, bridging exercises are associated with a risk of dominant hamstring and erector spinae muscle activity and excessive anterior pelvic tilt as a compensation for gluteus maximus muscle weakness regardless of the type of bridging exercise performed (4).

A study by Choi et al., (2015) studied the effect of isometric hip abduction (IHA) with the thera-band during gluteus maximus muscle activity and pelvic kinematics (or study of motion) during a bridging exercise. They found that gluteus maximus activity increased significantly (by 21.1%) during bridging with isometric hip abduction using a theraband. Applying IHA with a theraband during bridging and maintaining hip abduction with activation of the GM in advance before initiating the bridging movement consequently increases GM muscle activity.

Pilates and yoga exercises can help strengthening the lumbopelvic muscles which has been shown to improve lower back symptoms. Lumbopelvic stabilisation exercises have shown to be effective methods of pain management in chronic lower back pain patients as it has shown to improve pelvic stability through muscle strengthening and the ability to improve movement (6).

Hip and pelvis muscle strengthening exercises (glutes included) in addition to lumbar stabilization exercises increase hip joint stability, pelvic stability and increased range of motion, which is conducive to increasing strength and positively affecting low back symptoms (6).

Seated Gluteal Stretch:

References

1. Aurélio, M. N., de Freitas, D. G., Kasawara, K. T, Martin, R. L., Fukuda, T. Y. (2018) Strengthening the Gluteus Maximus in Subjects with Sacroiliac Dysfunction, Int. Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 13 (1): 114-120.

2. Barton, C. J., Lack, S., Malliaras, P., Morrisey, D. (2013) Gluteal Muscle Activity and Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systemic Review, J Sports Med, 47: 207-214.

3. Buckthorpe, M., Stride, M., Villa, F. D. (2019) Assessing and Treating Gluteus Maximus Weakness - A Clinical Commentary, Int. Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 14 ;(4): 655-669.

4. Choi, A-A., Cynn, H-S., Yi, C-H., Kwon, O-Y., Yoon, T-L.,Choi, W-J., Lee, J-H. (2015) Isometric Hip Abduction Using a Thera-Band Alters Gluteus Maximus Muscle Activity and the Anterior Pelvic Tilt Angle During Bridging Exercise; 25: 310-315.

5. Fisher, B. E., Lee, Y-Y., Pitsch, E.A., Moores, B., Southam, A., Saw, T. D., Powers, C. M. (2013) Method for Assessing Brain Changes Associated With Gluteus Maximus Activation, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43; 4: 214-221.

6. Gharib, S. (2020) Dead Butt Syndrome: Is It Real? https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346108868_Dead_Butt_Syndrome_is_it_real [online], last visited 28/12/2023.

7. Lewis, C. L., Foley, H. D., Lee, T. S., Berry, J. W. (2018) Hip-Muscle Activity in Men and Women During Resisted Side Stepping With Different Band Positions, Journal of Athletic Training, 53,;11: 1071-1081.

8. Meena, R., Doddamani, R. S., Singh, S., Singh, P., Agrawal. (2021) Exploration of Sciatic Nerve in the Gluteal Region: Transgluteal vs Infragluteal Approach, J Peripher Nerve Surg., 5: 34-37.

9. Nakagawa, T. H., Moriya, E. T. U., Maciel, C. D., Serão, F. V. (2012) Trunk, Pelvis, Hip, and Knee Kinematics, Hip Strength, and Gluteal Muscle Activation During a Single-Leg Squat in Males and Females With and Without Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 42, 6: 491-501.

10. Vannatta, C. N., Kernozek, T. W. (2018) Sex Differences in Gluteal Muscle forces During Running, Sports Biomechanics, 20; 3: 319-329.