Nerve Entrapment, Injury and Neuropathy; Ulnar Nerve

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 13 May, 2021

- •

Anatomy and Management

Individuals with compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve commonly describe symptoms of dysesthesia (altered sensations with numbness or paraesthesia/ tingling) of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger or atrophy and muscle weakness within the affected hand (3). The altered sensations are usually worse at night and begin intermittently particularly if the elbow is flexed whilst sleeping (3).

The ulnar nerve is broadly described as 'the nerve of the hand' as it innervates the majority of intrinsic hand muscles and is clinically significant for its role in hand function (4). The ulnar nerve is also the largest nerve in the human body to not be protected by either muscle or bone which is why injury is common (10).

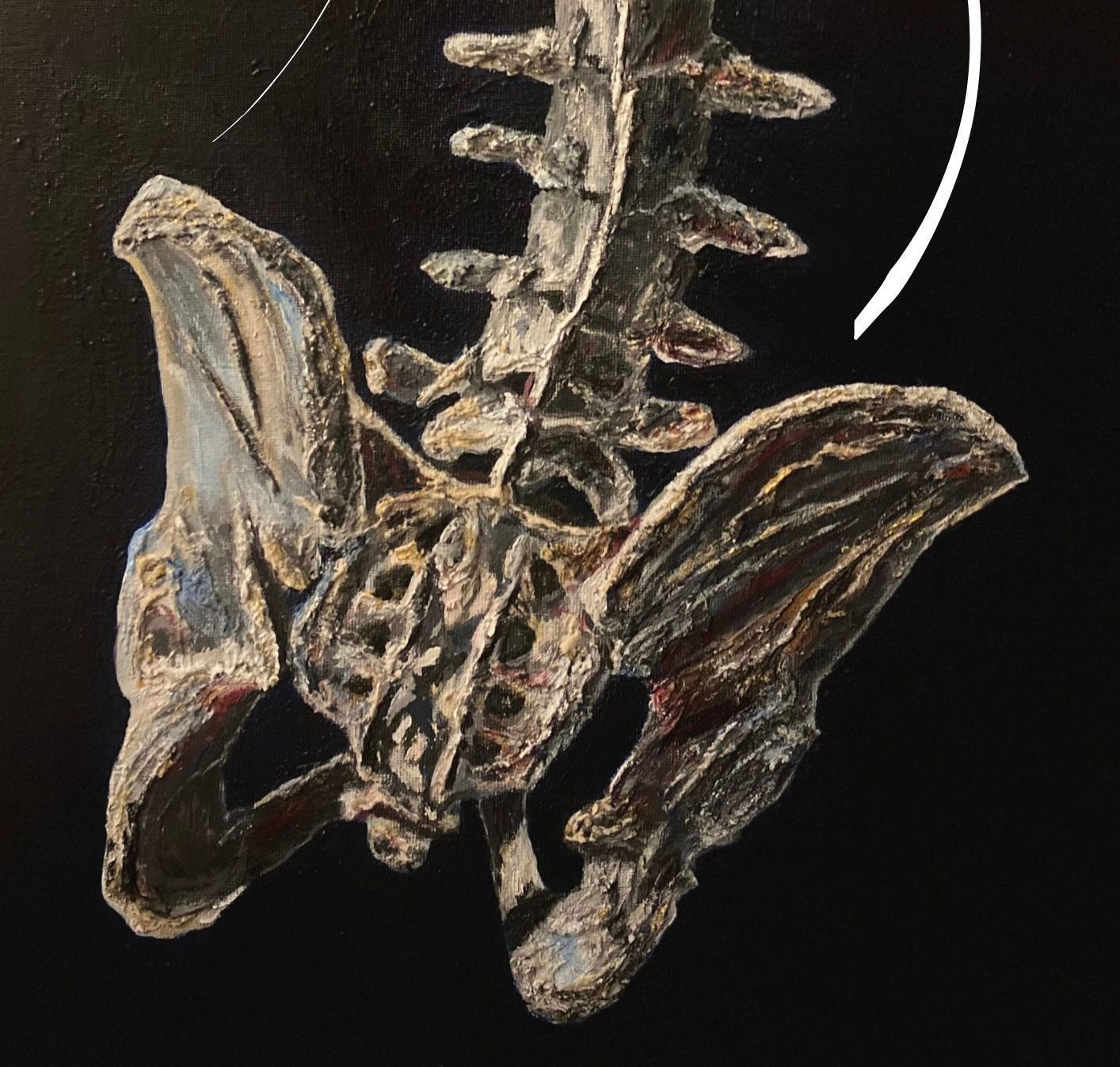

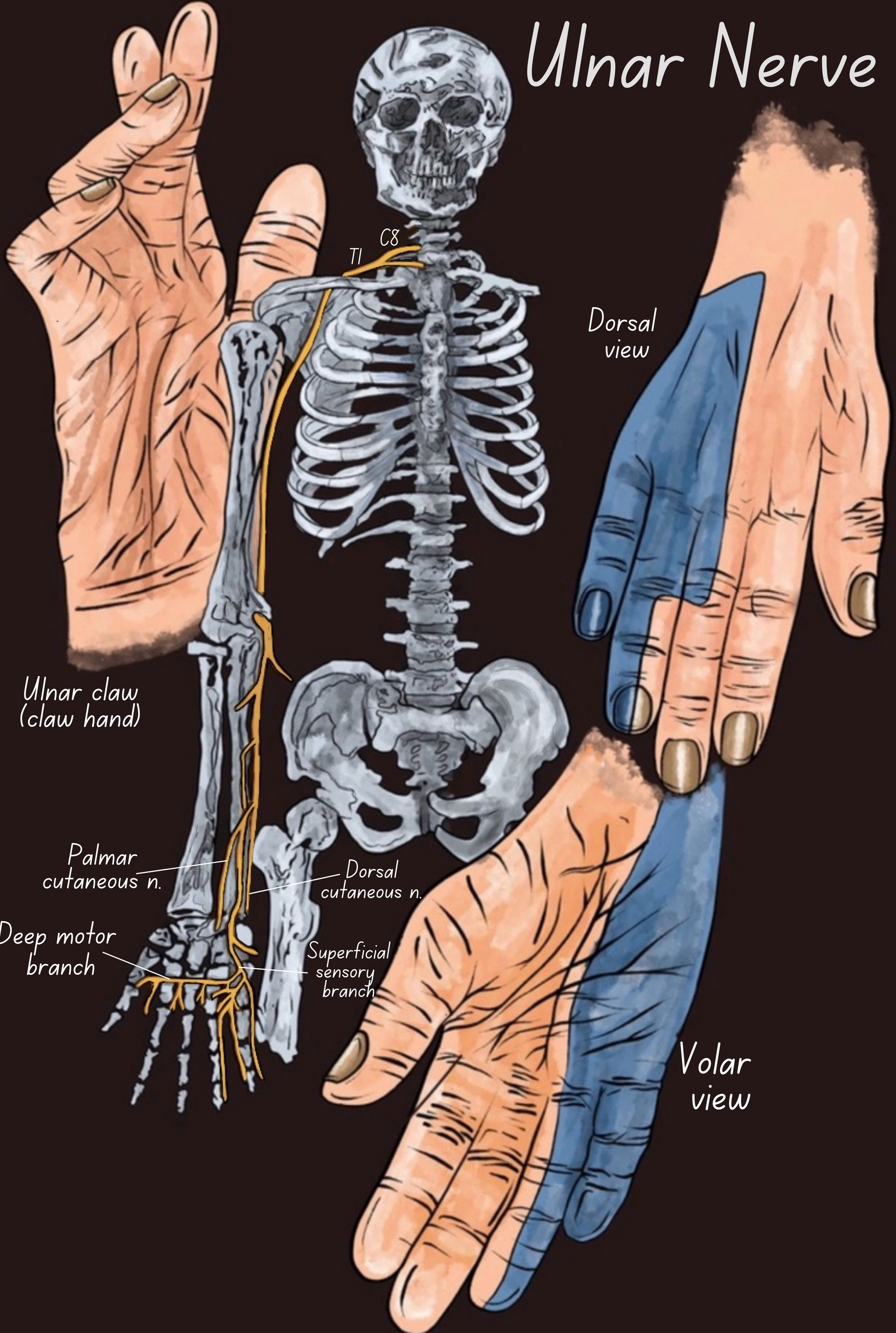

Most ulnar (and median) nerve palsies are as a result of traumatic transection which results in function impairment, can cause different levels of motor and sensitive dysfunction and is common in the upper extremity of young males (1). Significant injury to the ulnar nerve can lead to the characteristic presentation of a 'claw hand' (Figure 1). The ulnar nerve is also responsible for causing an 'electric shock' sensation by striking the medial epicondyle of the humerus posteriorly, or inferiorly with a flexed elbow. At this point, it can become trapped between the bone and the overlying skin and is commonly referred to as bumping one's "funny bone" (10).

Clinical Relevance of Ulnar Neuropathy

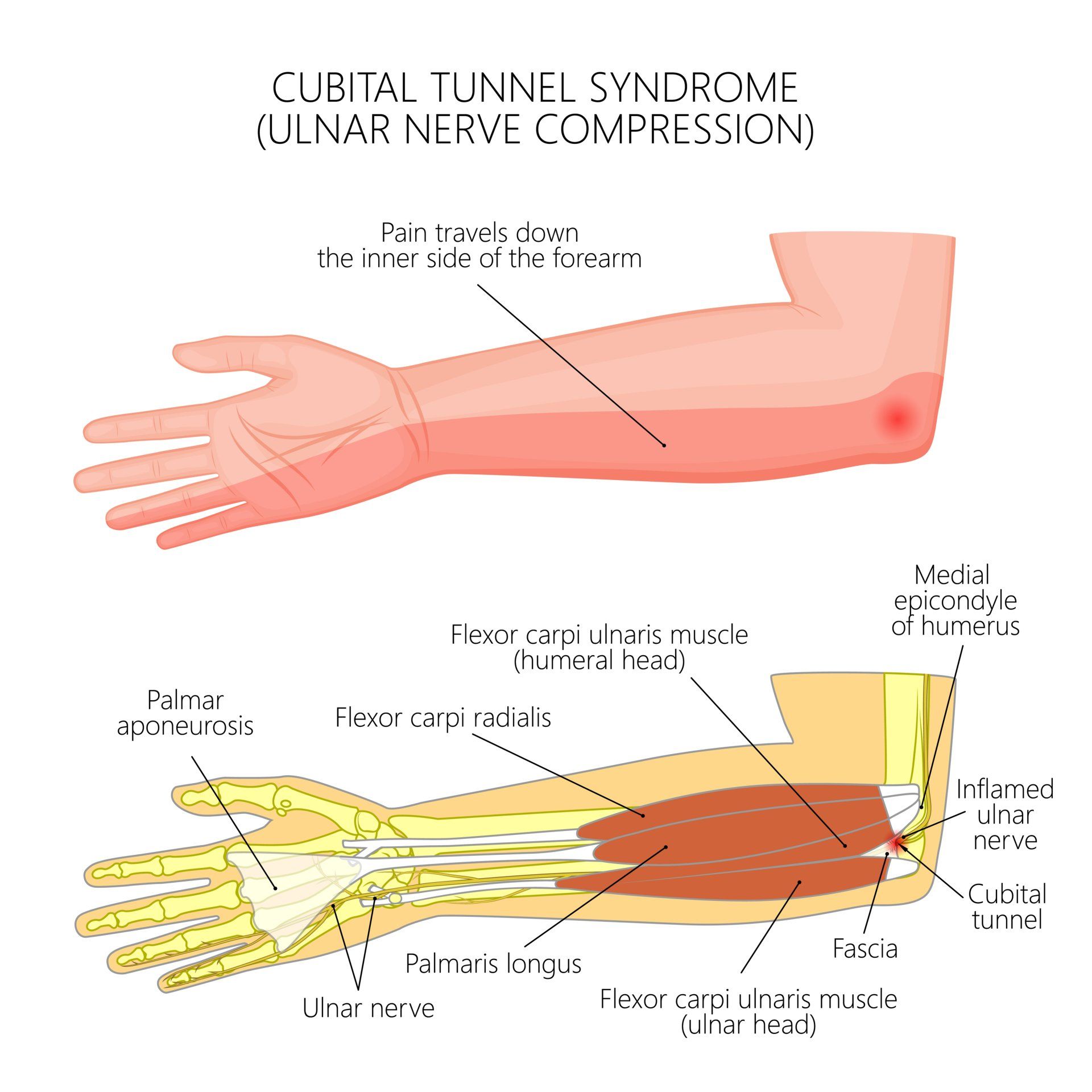

The ulnar nerve passes through several small spaces as it courses through the medial side of the upper extremity, and at these points the nerve is vulnerable to compression or entrapment. The nerve is particularly vulnerable to injury when there has been a disruption in the normal anatomy and the most common site of ulnar nerve entrapment is at the elbow (cubital tunnel syndrome), followed by the wrist (Guyon's canal syndrome) (7).

Causes or structures which have been reported to cause ulnar nerve entrapment or compression include (7):

- At the neck: thoracic outlet syndrome, cervical spine pathology, anterior scalene muscles.

- At the chest: pectoralis minor muscles.

- Brachial plexus abnormalities.

- Elbow: fractures, growth plate injuries, cubital tunnel syndrome, flexorpronator aponeurosis, arcade of Struthers.

- Forearm: tight flexor carpi ulnaris muscles

- Wrist: fractures, ulnar tunnel syndrome, ganglion, hypothenar hammer syndrome

- Artery aneurysms or thrombosis

- Other: Infections, tumors, diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatism, and alcoholism

While most cases of injury are minor and resolve spontaneously with time, chronic compression or repetitive trauma may cause more persistent problems. Commonly cited scenarios include (7):

- Sleeping with the arm flexed behind the neck or positioning the elbow in a prolonged flexed position.

- Pressing the elbows upon the arms of a chair while typing.

- Resting or bracing the elbow on the arm rest of a vehicle.

- Bench pressing.

- Intense exercising and strain involving the elbow.

Certain positioning of the elbow may create symptoms; cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the action of elbow flexion can cause the ulnar nerve to be predisposed to both compression and traction (2).

For laborers, tradesmen and women who have a physically demanding job andor throwing athletes who repetitively use their elbows, symptoms may be precipitated by intense or prolonged periods of increased activity. These individuals may also present with concurrent bony and soft tissue pathologies at the elbow, such as medial epicondylitis, lateral epicondylitis and ligamentous instability (5).

Anatomy & Nerve Course

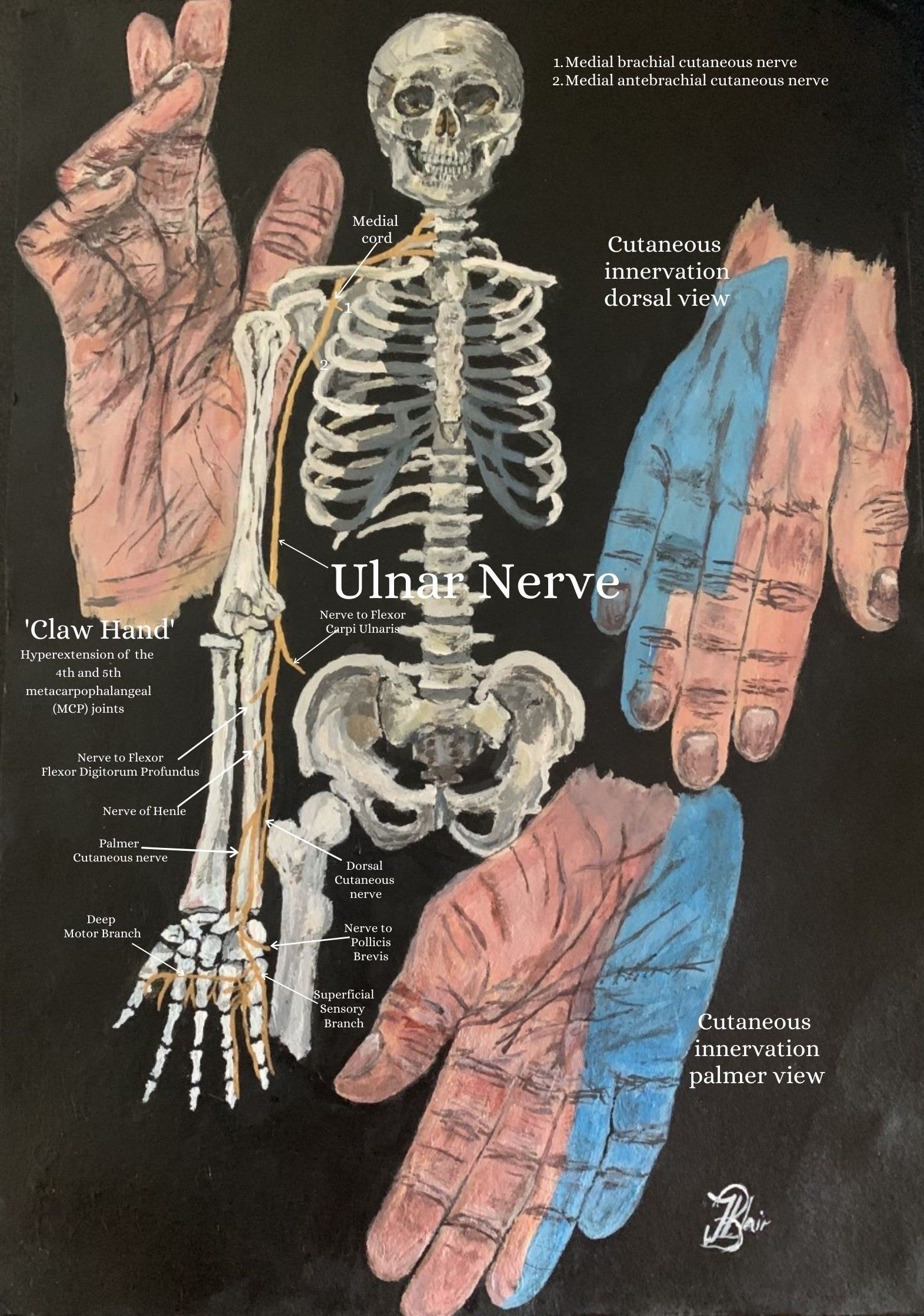

Being a terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus, it contains fibers from the ventral rami or the anterior division of C8 and T1 and can sometimes carry fibers from C7 (3, 5). The nerve travels distally through the axilla and is positioned medially to the axillary artery before descending the medial aspect of the upper arm (3).

Ulnar Nerve Journey Through the Arm

The ulnar nerve does not give branches in the upper arm or axilla, but starts giving muscular and cutaneous branches in the upper forearm and the hand (9). The nerve lays medially to the brachial artery and exits the posterior compartment of the arm before descending down the humerus to enter the anterior compartment of the arm through the medial intermuscular septum and runs anteriorly to the medial head of triceps brachii muscle (11).

Interestingly, in 70-80% of people, this nerve passes under the arcade of Struthers which is a thin aponeurotic band that extends from the medial head of triceps to the medial intermuscular septum which is another possible site for compression of the ulnar nerve (11, 3, 5).

Cubital Tunnel & Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

The borders of the carpal tunnel are (5):

- Medial wall – medial epicondyle of the humerus.

- Lateral wall – olecranon of the ulna.

- Floor – the elbow joint capsule and medial collateral ligament of the elbow.

- Roof – the cubital tunnel retinaculum or the arcuate ligament of Osbourne which runs between the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (2).

The cubital tunnel is yet another site for compression of the ulnar nerve and is the second most common peripheral neuropathy of the upper limb (after carpal tunnel syndrome) (2).

Ulnar Nerve Journey; the Forearm

The ulnar nerve passes between the medial epicondyle and olecranon in the groove for the ulnar nerve to enter the anterior compartment of the forearm (6). Posterior to the medial epicondyle, the ulnar nerve is easily palpable and is commonly referred to as the "funny bone" in this region (6).

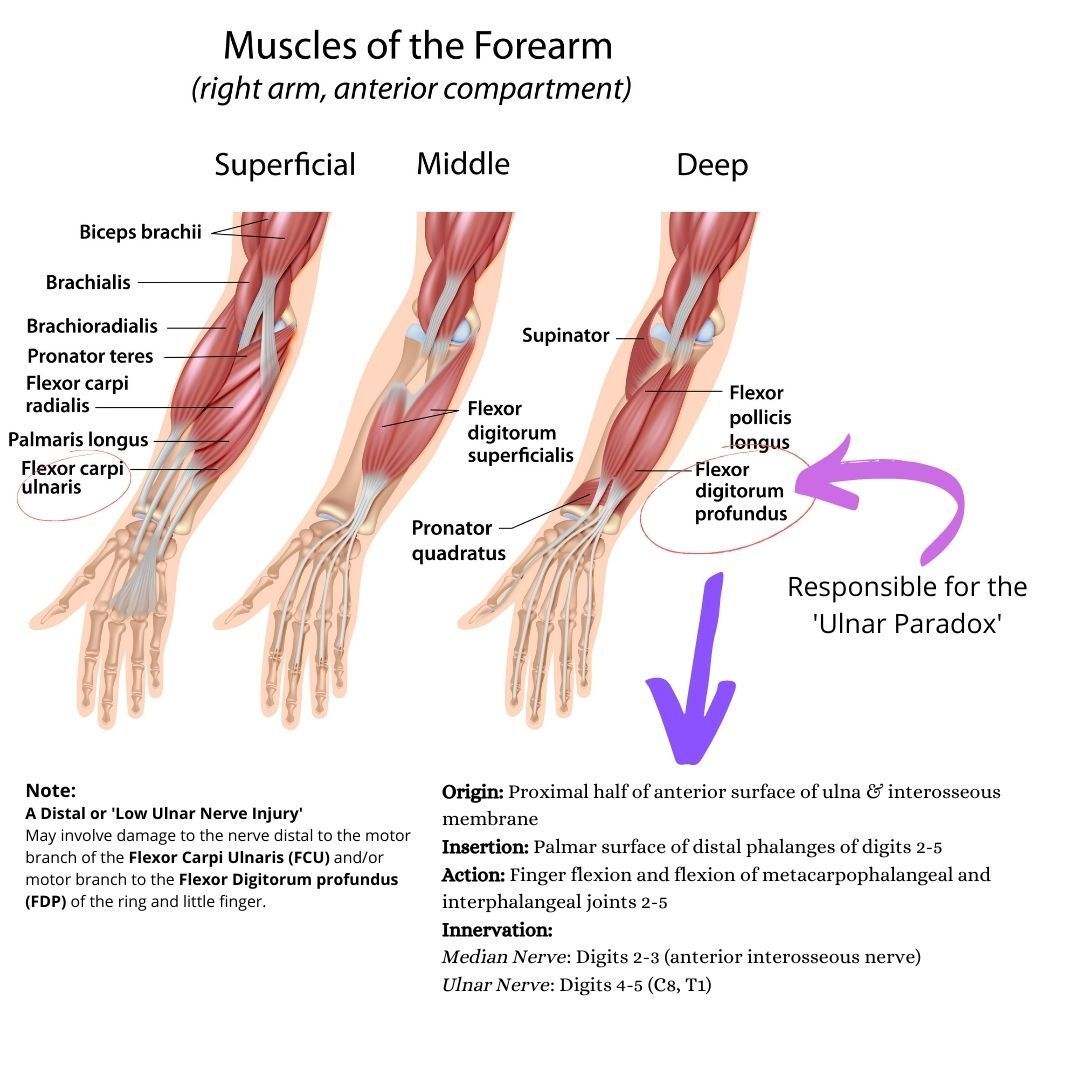

After exiting the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve gives off 2 or 3 muscular branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) muscle. The ulnar nerve passes beneath the humeral and ulnar heads of the FCU muscle to enter the volar aspect of the forearm, where it continues deep to the flexor pronator aponeurosis. In the forearm, the nerve passes anterior to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) muscle to supply motor branches to the ulnar half of FDP. The ulnar nerve travels the remaining length of the forearm between the FDP and the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) muscles (5, 6).

Ulnar Nerve Branches At the Wrist & Hand

Proximal to the wrist, the dorsal cutaneous nerve branches off to the dorsal hand followed by the palmar cutaneous branch to the proximal palm (8). These two sensory branches to the hand do not pass through the Guyon's canal (8).

The Dorsal Cutaneous Branch arises from the medial aspect of the ulnar nerve approximately 8cm proximal to the pisiform bone and provides dorsal branches to the little finger, the lunar aspect of the ring finger and the ulnar aspect of the carpus and hand (11).

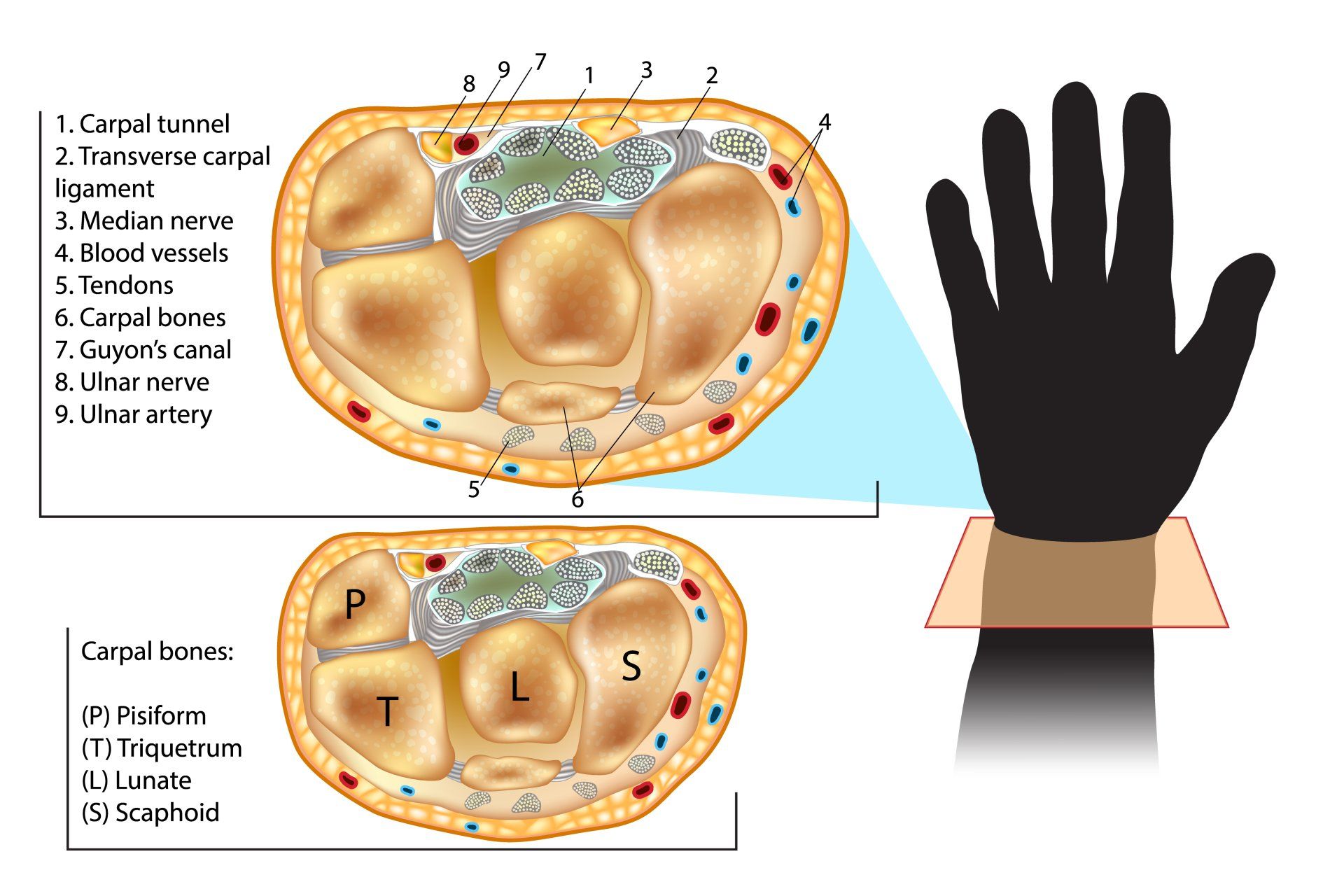

The Guyon's Canal

The ulnar nerve and artery then enter the hand by travelling through the Guyon's canal (or ulnar canal) which is a groove between the pisiform and hook of the hamate and bridged by the palmer carpal ligament (5).

At the distal aspect of the Guyon's Canal and as the ulnar nerve exits under the palmaris brevis muscle, the ulnar nerve bifurcates into the superficial sensory branch and the deep motor branch (11).

Deep Motor Branch of the Ulnar Nerve

The deep motor branch passes between the flexor and abductor digiti minimi (ADM) muscles and gives off a branch to the hypothenar muscles, including the ADM. The Deep motor branch then turns about the hook of the hamate and deviates laterally across the palm to innervate the dorsal interossei, the third and fourth lumbricals, the adductor pollicis (AP), the flexor pollicis brevis (FPB), and terminates in the FDI (8).

Superficial Branch of the Ulnar Nerve

Supplies sensation to only the ulnar surface of the hypothenar eminence, the ulnar half of the fourth digit and the fifth digit (8). The superficial branch of the ulnar nerve gives off two small motor branches to the palmaris brevis muscle (11).

Guyon's Canal Syndrome

Cyclists who place prolonged pressure against bicycle handlebars (also known as handlebar neuropathy) along with various sports and activities such as weight lifting who experience repetitive trauma and place pressure on the hypothenar eminence are at an increased risk for compression of the ulnar nerve at the Guyon's canal (3, 6, 8). This form of ulnar neuropathy comprises of two work-related syndromes: so-called "hypothenar hammer syndrome," seen in workers who repetitively use a hammer, and "occupational neuritis" due to hard, repetitive compression against a desk surface (7).

Incidences And Location of Ulnar Neuropathy

A listed summary of sites are (7):

- The medial epicondyle

- The cubital tunnel (most common)

- Guyon's canal

Proximal/ High Ulnar Nerve Injury (Closer to the Elbow)

In high injuries, the nerve is damaged above the origin of the motor branch of the FCU and FDP muscles. A high ulnar nerve injury results in less claw hand deformity as the loss of FDP function (6, 7).

Proximal Ulnar Nerve Compression; often occurs when a person rests their elbow on the table for a long time, or on a window (for long distance drivers). It can also occur as an athletic injury, particularly in throwing athletes e.g. baseball pitchers, cricketers, and javelin throwers. The rapid movement of the elbow joint from flexion into whip-like extension can results in compression of the ulnar nerve (6).

Distal/

Low Ulnar Nerve Injury (Closer to the Hand)

Re-examining the ulnar nerve anatomy, a distal or 'low ulnar nerve injury' can

involve damage to the nerve distal to the motor branch of the Flexor Carpi

Ulnaris (FCU) and/or motor branch to the Flexor Digitorum profundus (FDP) of

the ring and little finger (11). As a result, sensibility to the palmar ulnar

hand is lost and paralysis commonly occurs to all 7 interosseous, the ulnar 2

lumbrical muscles, the 3 hypothenar, the adductor pollicis, and the deep head

of the flexor pollicis brevis muscles (11).

The Ulnar Paradox

The ulnar nerve innervates the ulnar (medial) half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle (FDP) of the forearm which flexes the forearm and the fingers (figure 5).

Proximal (High) Ulnar Nerve Injury

Proximal (or high) ulnar nerve lesions are commonly as a result of trauma at or above the elbow and cause palsy and denervation of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) muscle (1, 7).

However, a proximal injury leads to an open palm and there is more capacity for hand function (6). As a result, flexion of the IP joints are weakened and this reduces the claw-like appearance of the hand. Instead, the fourth and fifth fingers are paralysed in their fully extended position (6, 7).

Distal (Low) Ulnar Nerve Injury

This is opposite to a distal injury in the hand which denervates muscles that flex the hand. This is called the "ulnar paradox" as one would expect a proximal ulnar nerve injury to result in a more debilitating and deformed appearance. As re-innervation occurs along the ulnar nerve and the patient recovers after a proximal (high) lesion. In a proximal injury, the deformity will at first get worse (as the FDP will be re-innervated) - hence the use of the term "paradox" (7). A simple way to remember this is: 'the closer to the Paw, the worse the Claw' (10).

'Claw Hand'

Individuals with the claw hand deformity have hyperextension of the 4th and 5th metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints due to the denervation of the 3rd and 4th lumbricalswhich flex the MCP joints (7|). The unopposed action of the long finger extensors cause these joints to be extended by the long finger extensors; extensor digitorum and the extensor digiti minimi (7).

The lumbricals and interossei also extend the interphalangeal (IP) joints of the fingers by insertion into the extensor hood and their paralysis results in weakened extension (7). The combination of hyperextension at the MCP and flexion at the interphalangeal (IP) joints (Duchenne's sign) gives the hand its 'claw' like appearance (7, 11).

Examination

To better understand the deficiency associated with low ulnar nerve palsy, 5 areas of pathology are explored (3):

- pinch

- digital motion

- grip

- clawing of the ring and little finger

- digital abduction/adduction.

In cases of advanced ulnar neuropathy, further inspection may reveal atrophy in the hypothenar eminence and in the first dorsal interosseous muscle bulk (3).

Clinical Tests

- Froment’s sign : overt flexion of the thumb interphalangeal joint while attempting resisted pinch (3)

- Wartenburg’s sign Persistent abduction posture of the small finger due to unopposed action of the radial-innervated extensor digiti minimi (3).

- Tinel’s sign; Percussion testing over the areas of entrapment sites.

- Direct pressure applied over known compression points of the nerve. The most sensitive (91 %) provocative test for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is direct pressure over the ulnar nerve posterior to the medial epicondyle while the elbow is in flexion (3).

- Scratch collapse test to identify distinct or concurrent points of ulnar nerve compression (3).

- Ten Test: Sensory examination with subjective responsiveness to sensation to light touch (3).

- Muscle Power Testing: motor examination of the flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus, finger abduction and finger adduction.

- Two point discrimination.

Treatment and Management

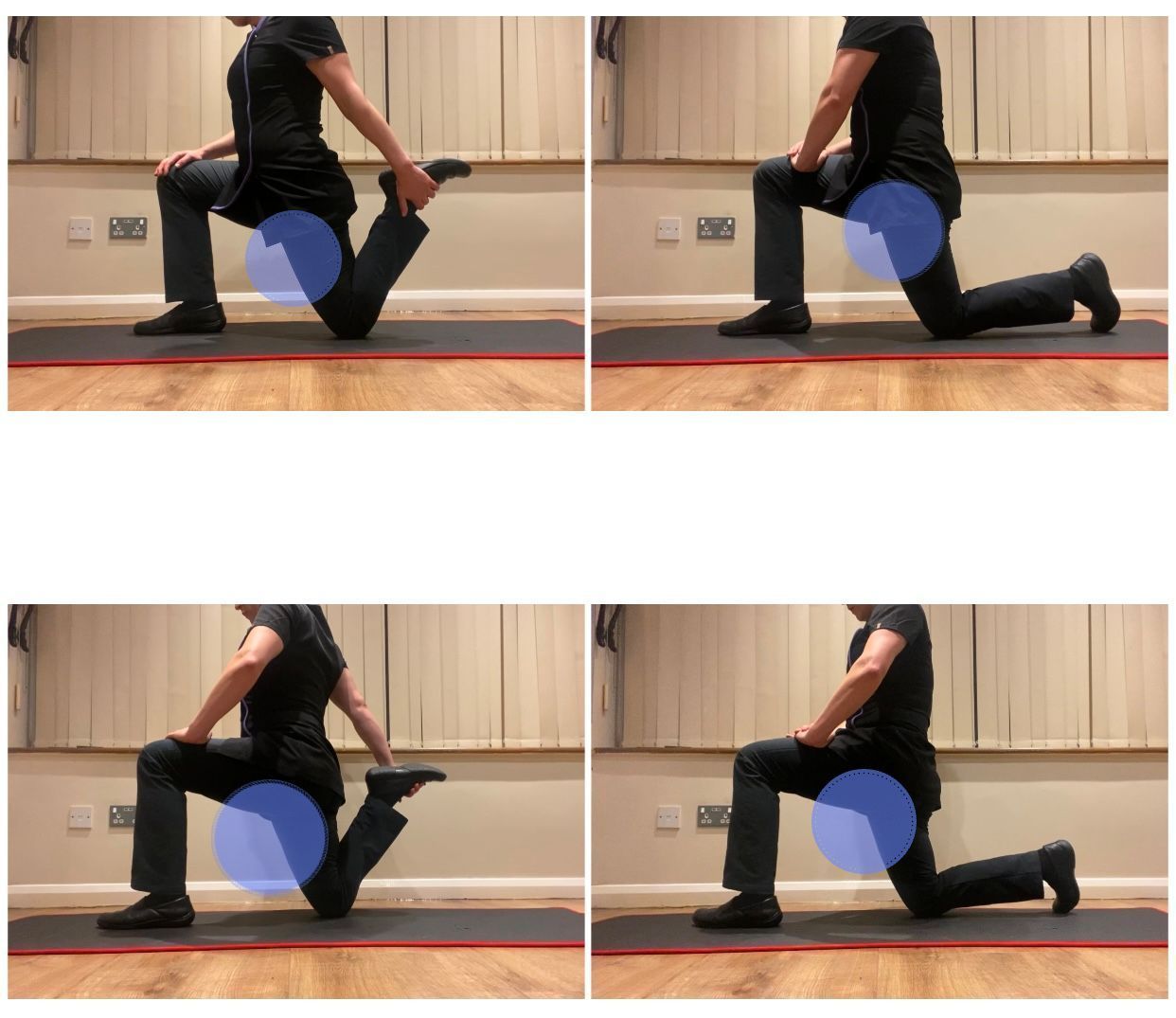

Ulnar Nerve Flossing Exercise:

The use of splints in peripheral-nerve injury, specifcally for the ulnar nerve should have the following aims (1);

- Keeping the denervated muscles from remaining in an overstreched position.

- Prevent joint stiffness.

- Develop strong movement patterns and to maximize functional use of the hand (1).

- The goal in splinting a low lesion of ulnar nerve is to prevent overstretch of denervated intrinsic muscles of the ring and little fingers (1).

- Splints that blocks the MP joints in slight flexion prevent de claw deformity by forcing the extrinsic extensor to transmit forces into the dorsal hood mechanism of the finger (1).

Assessment of the posture and placing careful attention to head, cervico-thoracic spine, scapula, upper and lower arm positioning will be of great importance. One must take into consideration the uniqueness of each case and techniques might be applied around the known entrapment site. Techniques may involve soft tissue techniques to the areas already mentioned along to the axilla, ribs/ intercostal and erector spinae muscles. Gentle articulation and osteopathic techniques might also be applied along with electrotherapy and kinesiology taping to encourage enhanced postural positioning.

References

1. Barbosa, R. I., Fonseca, M. de C. R., Valéria, V. M. C., Mazzer, N., Henrique, C. (2012) Median and Ulnar Nerves Traumatic Injuries Rehabilitation, Basic Principles of Peripheral Nerve Disorders, Chapter 15, Available From: https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/34135/InTech-Median_and_ulnar_nerves_traumatic_injuries_rehabilitati... [Last Accessed 09/05/2021].

2. Becker, R. E., Manna, B. (2020) Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Ulnar Nerve, Available From: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499892/ [Last Accessed 03/05/2021].

3. Dy, C. J., Mackinnon, S. E. (2016) Ulnar Neuropathy: Evaluation and Management, Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med, Springer, 9: 178-184.

4. Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation (2020) Cubital Tunnel Syndrome, Available From: https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/therapies/hand-therapy/cubital%20tu... [Last Accessed 11/05/2021]

5. Jones, O. (2021) The Ulnar Nerve, Teachmeanatomy, Available From: https://teachmeanatomy.info/upper-limb/areas/ulnar-tunnel/ [Last accessed 03/05/2021]

6. Kenhub (2020) The Brachial Plexus, Available From:

https://www.kenhub.com/en/study/the-brachial-plexus [online; last viewed 18/10/2020].

7. Neurology Needs, Ulnar Nerve, Available From: https://www.neurologyneeds.com/neuroanatomy/peripheral-nerves/ulnar-nerve/ [Last Accessed 12/05/2021]

8. Pearce, C., Feinberg, F., Wolfe, S. W. (2009) Ulnar Neuropathy at the Wrist, HSSJ, 5: 180–183, Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26276661_Ulnar_Neuropathy_at_the_Wrist, [Last accessed 03/05/2021]

9. Physiopedia. Ulnar Nerve. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Ulnar_Nerve [last accessed 03/05/2021]

10. Wikipedia (2021) Ulnar Nerve,Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, Available From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulnar_nerve [Last Accessed 03/05/2021]

11. Woo, A., Bakri, K., Moran, S. L. (2015) Management of Ulnar Nerve Injuries; Current Concepts, ASSH, Journal of Hand Surgery Am., 40: 173-181.