Cardiological Signs and Symptoms and Referred Shoulder Pain; A Case Study Analysis

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 07 Feb, 2023

- •

Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) and Related Referred Shoulder Pain

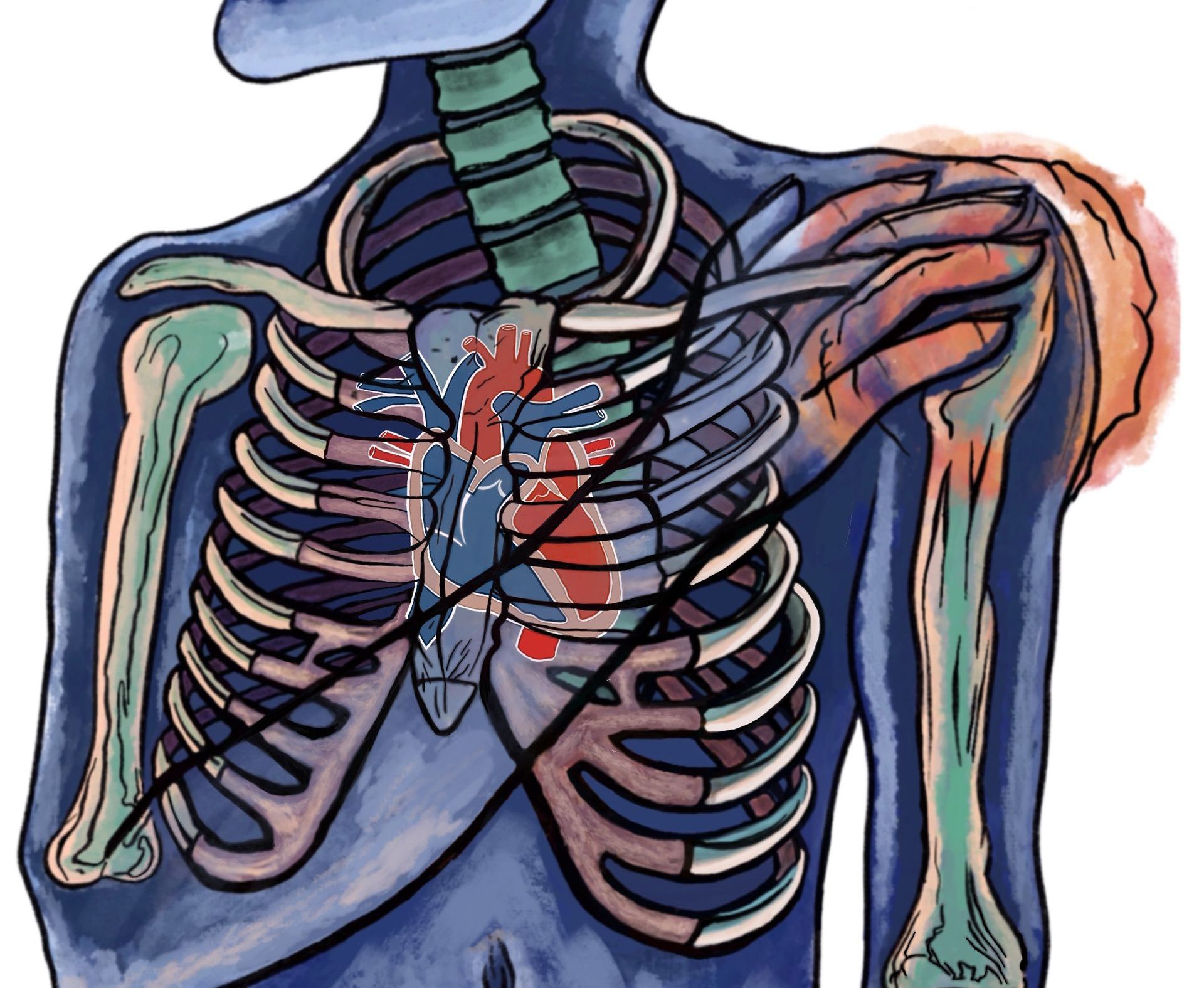

However, in addition to musculoskeletal or mechanical origin of pain, healthcare professionals must be aware of visceral or serious potential life-threatening illnesses that may refer pain to the shoulder, such as cardiovascular disorders. Patients with cardiovascular pathologies, especially for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), commonly present with either chest, upper limbs or abdominal pain. Other sites of pains may present with the following signs and symptoms (1):

- Crushing, substernal chest pain

- Jaw pain

- Neck pain

- Diaphoresis (excessive sweating)

- Dyspnea

- Fatigue

Unfortunately, the above listed signs and symptoms could lead to a misleading diagnosis of other pathologies even within an emergency department (ED). This post may help highlight why careful questioning and attention to detail of patient case history taking is so important to establish when shoulder pain could be an indicator for a cardiological visceral somatic cause (2).

Acute Myocarditis Case Study; Summary and Discussion

Over a short nine day period, he overall attended two appointments at the emergency department for continuous right shoulder pain who diagnosed right MSK shoulder syndrome on both occassions. He was given an intramuscular injection of diclofenac during his first visit and prescribed an infusion of saline solution (100 mL and 250 mL), ranitidine hydrochloride (50 mg/5 mL) and diazepam (10 mg). Upon discharge, the patient was also advised to take eperisone hydrochloride (100 mg) twice and ibuprofen (600 mg) twice a day for 5 days, rest from work for 1 week and a prescription of antalgic electrotherapies.

First Physiotherapy Appointment

He then attended a physical therapy appointment. The physical therapist observed how the client arrived at the clinic holding his upper limb in an antalgic posture, with 'his arm adducted and internally rotated using a foulard knotted behind the neck'. The physiotherapist recorded limited shoulder joint active and passive ranges movement of 70 degrees whilst performing elevation and abduction and gave him exercises to help with the pain.

Second ED Appointment

On the same evening of the physiotherapy appointment, the patient attended the emergency department (ED) for a second time due to a reoccurrence and increase in pain. The patient's BP was 110/90 mmHg, RR of 16 rpm, HR of 98 bpm and the ED again recorded unremarkable clinical findings, gave the same diagnosis as the first ED appointment and performed an intramuscular injection of thiocolchicoside (4 mg/ 2 ml) and diclofenac (75 mg/ 3 ml) for pain-relief. Upon discharge, the patient was instructed to perform a daily intramuscular injection with the same dosages and drugs.

Second Physiotherapy Appointment

The morning of the day after the ED and physiotherapy appointments and the ninth day post onset of his original right shoulder pain, the patient went back to visit his physical therapist for the second time. He reported a change of symptoms with that his pain had shifted from his right shoulder into his left shoulder and the left pectoral region along with constant radiating and oppressive radiating pains (NPRS = 9/10) down his left upper limb. Furthermore, he was experiencing symptoms of dyspnea , fatigue, shortness of breath and diaphoresis (excessive sweating). His physical therapist correlated the current new symptoms to a suspected underlying cardiovascular condition and referred him to his general practitioner who referred him back to the emergency department after suspecting an acute myocardial infarction.

Third ED Appointment Testing and Results:

On admission at the emergency department, the patient underwent a third medical assessment. His vitals were BP of 130/90 mmHg, HR of 98 bpm, RR of 25 rpm, pulse oximetry saturation levels were 97%. Neurologic and pulmonary systems were normal and abdominal palpation revealed minimal tenderness in the epigastric region.

During the cardiologic visit a 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) and routine blood test was performed and revealed findings for the need of further drastic cardiological treatment and surgery.

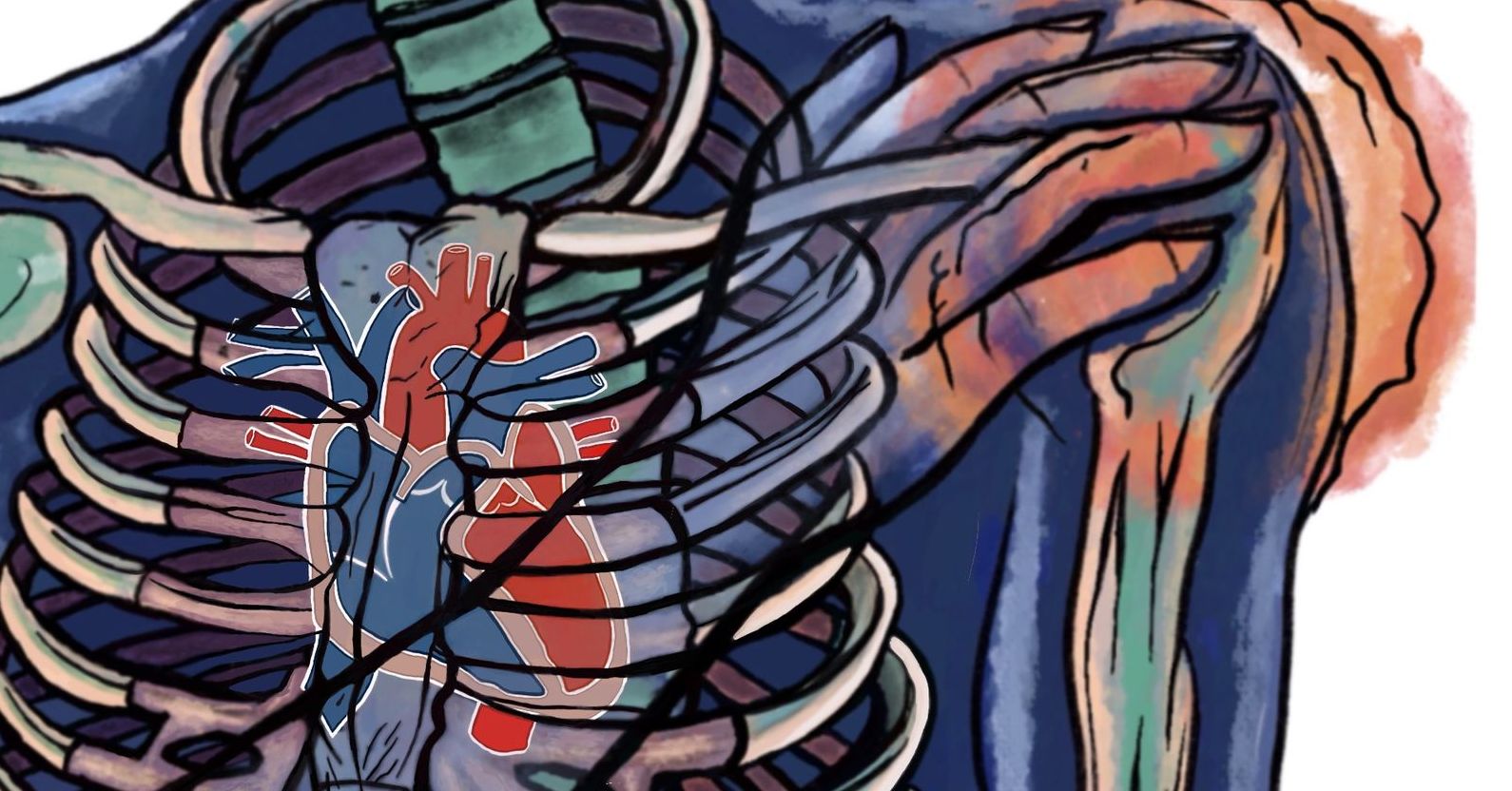

- The ECG showed elevation of the ST-segment. The ST segment represents the interval between the depolarisation of the ventricles and an elevation indicates a blockage (or occlusion) of the involved coronary artery.

- A low voltage of the QRS complex was also found which can be caused by the “damping” effect of increased layers of fluid, fat or air between the heart and the recording electrode.

- High levels of cardiac troponin 4.9 ng/mL was detected (with normal ranges being 0-0.04 ng/mL). Very high levels of troponin are a sign that a heart attack has occurred and most patients who have had a heart attack have increased troponin levels within 6 hours. After 12 hours, almost everyone who has had a heart attack will have raised levels. Troponin levels may remain high for 1 to 2 weeks after a heart attack.

- Bedside echocardiogram and color Doppler showed anterolateral septal-apical necrosis (Anterior wall myocardial infarction is often caused by occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery).

- Severe left ventricular dysfunction and right pulmonary arterial hypertension.

- A coronary angiography demonstrated a complete occlusion of the proximal portion of left anterior descending artery (LAD).

The patient was admitted to the intensive cardiologic care unit with a diagnosis of acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction due to occlusive coronary artery disease. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) was performed to open the blocked coronary arteries to improve blood flow to the heart muscle and a drug-eluting stent (DES) on LAD was planted in the cath lab immediately after.

After a week of hospitalization in the surgical unit, the heart surgeon decided to subject the patient to the implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) due to persistent arrhythmia.

At 3 months follow-up, ICD has been evaluated and no signs of intervention were detected. Furthermore, neither signs nor symptoms of shoulder pain or viscerogenic disease had been reported. Thereafter, the cardiologist allowed performing a cardiological physiotherapy program and the patient made a full recovery after six months.

Further Study Discussion:

Medication intake of non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patient cases with a suspected cardiovascular disease is potentially an aggravating factor in the case of an acute myocardial infarct (AMI). Specifically, diclofenac-based medications should be carefully administered under medical prescription due to their high cardiovascular associated risks.

Moreover, attention must be given to patients who use other NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or paracetamol, which despite having shown lower risks of cardiovascular events than diclofenac still pose a substantial aggravating risk in the case of an AMI.

In this case, the patient's prescription of listed NSAIDs listed above could have accelerated his symptoms and contributed to the sudden shift and change of symptoms from the right shoulder pain to the left shoulder. Other red flags noted was a consistent blood pressure diastolic reading of over 90 mmHg and an idiopathic non specific recent cause for constant right shoulder pain.

It is appreciated, however, that it was difficult to distinguish the present shoulder pain caused via a visceral somatic pathology and a previous history of multiple shoulder dislocations. In this case, other signs and symptoms including dyspnea, fatigue, shortness of breath and diaphoresis established the final need for a referral. It has also been observed that clients should be encouraged to regularly self monitor their own blood pressure should a practitioner suspect a cardiological visceral somatic cause as a differential diagnosis for a related musculoskeletal complaint.

References

1. Lin, K-T., Lai, S-W., Hsu, S-D., Fan, C-Y., Wang, H-J., Chang, P-K., Wei‐Hsiu Liu, W-H., Chen, Y-L., Yen, I-C., Lee, S-Y. (2019) Shoulder Pain and Risk of Developing Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease: A Nationwide Population‐Based Cohort Study in Taiwan, J Med Sci, Wolters Kluwer, MedKnow; 39; (3):127-134.

2. Storari, L., Barbari, V., Brindisino, F., Testa, M., Filippo, M. (2021) An unusual Presentation of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Physiotherapy Direct Access: findings From a Case Report, Archives of Physiotherapy, 11; (5): 1-9.