Scapula Dyskinesis & Shoulder Pain

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 28 Mar, 2024

- •

Categories, Cause, Testing & Rehabilitation

Scapula dyskinesis (SD) can be quite a complex topic and challenging to manage for practitioners. For patients who have been found to have this condition; re-education and retraining scapula positioning requires patience, time and practising exercises on a daily basis.

Scapula dyskinesis is a term used to describe improper movement and positioning of the scapula (or shoulder blade) during shoulder movement (5). The word ‘dyskinesis’ is Greek, with ‘dys’ meaning the alteration of and ‘kinesis’ translating as motion.

Sciascia and Kibler (2022) highlight how scapula dyskinesis is not an injury as it relates to being a physical impairment and the term should not be used as a musculoskeletal diagnosis. An alternative term often used for this disorder is ‘dyskinesia’, however, Roche et al., (2015) note that this expression is less accurate as it implies abnormal active movements mediated by neurological factors.

Dyskinesis, however, is more inclusive with incorporating various other factors that may be causative for this condition such as glenohumeral angulation, AC joint strain, subacromial space dimensions, shoulder muscle activation and humeral positioning and motion (9).

The positioning of the shoulder blade or scapula contributes to both mobility and stability of the neck and shoulder region, current clinical evidence suggests a strong relationship between SD with chronic neck and shoulder pain (8).

In clinical practice, scapula dyskinesis is identified by the presence of the prominence of the border of scapula which includes superior, medial, or inferior borders and a loss of scapula control during bi-planar arm movements i.e. during flexion/extension and abduction movements (8).

Scapula dyskinesis is not to be confused with scapula “winging” as this is best reserved for altered scapular motion driven by neurological compromise (9).

Hickney et al., (2018) discovered that individuals with SD had a 43% greater risk of developing shoulder pain than those without SD. Panagiotonopoulos and Crowther (2019) note how most common shoulder pathologies are associated with some form of scapula dyskinesis including:

1. Acromioclavicular instability

2. Shoulder impingement

3. Rotator cuff injuries

4. Glenoid labrum injuries

5. Clavicle fracture

6. Nerve-related pain e.g. nerve entrapment.

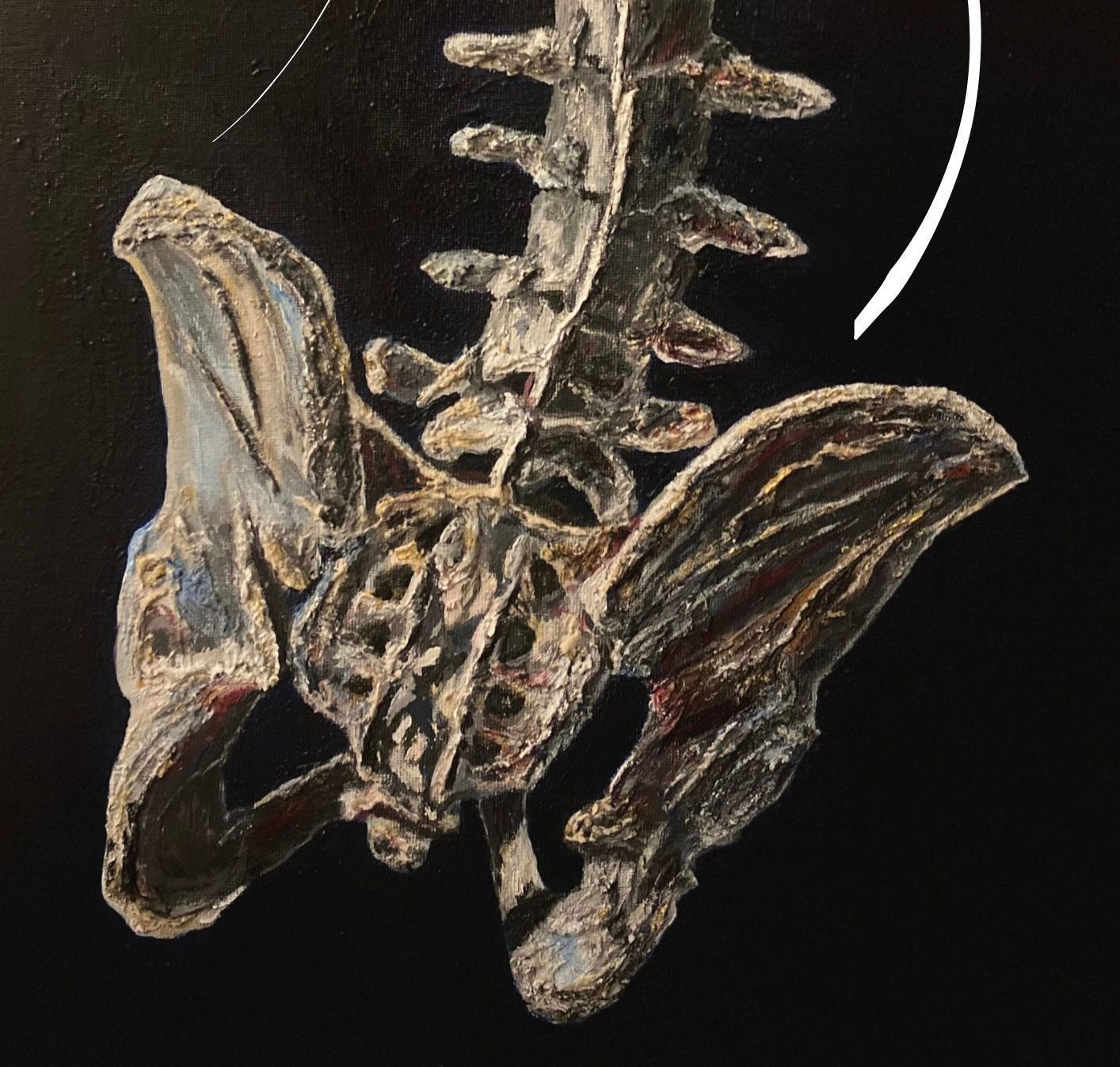

SD & Three Categories

Abnormal patterns of movement in scapula dyskinesis can be observed by determining the position of the scapula with the patient’s arms resting on their side (2). A shadow that can be seen within the left inferior border of the scapula within the image above may indicate its presence.

Dynamic scapula motion testing (DSMT) can be used to understand the mechanics of scapula dyskinesis by lowering and raising the arm to 120 degrees with or without holding weights (8, 2). Abnormal scapula movement can be divided into three categories of dyskinetic patterns which can aid rehabilitation and recovery for the flexibility required by certain muscle groups.

Three types of scapula dyskinesis according to Kibler et al., (2002) are:

1. Type I is characterised by increased prominence of the inferior and medial prominence (lower angle) of the scapula. This can usually be observed during scapula rotation moving about a transverse axis.

2. Type II is characterised by representing abnormal rotation about a vertical axis, i.e. during movements of medial and lateral rotation, abduction/ adduction of the shoulder. An increased prominence of the whole medial part of the scapula can be observed.

3. Type III is characterised by the prominence of the upper and medial borders of the scapula.

Normal, symmetric scapular motion is considered type IV.

Kibler et al., (2002) suggested that mild scapular dyskinesis is more frequently evident during the lowering phase of arm movement. It is presumed that this is because of the altered neuromuscular control required during eccentric muscle contraction (3).

Cause

Several factors can create changes in the position of the scapula including (7):

- Poor posture.

- Excessive resting posture.

- Thoracic and cervical kyphosis.

- Lumbar spine lordosis resulting to excessive scapular and acromial protraction.

- Traumas including clavicle fractures and acromioclavicular joint injuries.

- Glenohumeral joint instabilities.

- Osteoarthritis

- Changes in the function of the muscles that control the scapula.

- Lesions along the long thoracic nerve, and spinal nerve injuries (7).

Testing For Scapula Dyskinesis

Examination usually involves clinical observation of the scapula positioning to determine whether a prominence can be seen within the inferior or medial borders of the scapula.

Assessment for scapula prominence is carried out by observing a lack of smooth coordinated movement of the scapula during forward flexion, shrugging or arm lowering from a position of full flexion (6).

Clinical tests may involve the following (6):

1. Scapula Retraction Test (SRT) (6): Performed during GHJ lateral rotation.

The clinician's hand manually stabilises the medial border of the scapula in a retracted position on the thorax and the client's arm is raised or rotated externally. When there is relief of symptoms, the test is considered positive. This test frequently demonstrates scapula and glenoid involvement in impingement lesions.

Evaluates glenohumeral joint impingement and rotator cuff strength. The practitioner assists scapula elevation by manually stabilising and rotating the inferior border of the scapula during humeral abduction. This procedure simulates the activity of the serratus anterior and lower trapezius muscles. If symptoms of impingement are diminished or eliminated by this manoeuvre, then it is considered a positive test.

This testing evaluates three different positions of the scapula in relation to a fixed point on the spine. These positions offer a graded challenge to the functioning of the shoulder muscles to stabilise the scapula.

- The first position is with the arms by the side. The inferomedial angle of the scapula is palpated and marked on both the injured and non-injured sides. The measurements from a fixed reference point are recorded.

- The second position is with the hands on the hips with approximately 10 degrees of shoulder extension. The position of the inferomedial border of the scapula is marked, a reference point on the spine is made (i.e. spinous process of a vertebrae) and the distances are calculated on both sides accordingly.

- The third position involves the arms held at or below 90 degrees of flexion with maximal internal rotation at the glenohumeral joint. The threshold of abnormality is 1.5 cm and significant asymmetry is measured.

An essential part of scapula examination is the evaluation of the shoulder pathology or injury that could be causing or exacerbating the presence of scapula dyskinesis. Rotator cuff strength, labral stability and internal impingement should be examined as they may represent the underlying cause of scapula dyskinesis (6).

Rehabilitation

Clients tend to find scapula repositioning exercises challenging as they are unable to visualise the scapula and its posterior location on the thorax. It is possible that the lack of visual feedback leads to the alterations in motion to cause scapula dyskinesis. Repositioning the scapula prior to elevating and/or rotating the humerus, called conscious correction increases scapula muscle activity and enhances scapula kinematics (6).

1. Short lever progression

An example of short lever exercise application would be to begin with exercies that require the arms to be in an adducted position i.e. the arms position against the thorax rather than positions that require the arms to be elevated or abducted for exercise performance. These early interventions attempt to establish proper scapula positioning early in the rehabilitation and begin to utilise the major of kinetic chain segments to create the integrated muscle activation and sequencing.

Although they could be classified as short lever exercises, maneuvers such as scapula shrugging or elevation should be avoided in the first 4-6 weeks of rehabilitation (6). This is intentional to not overly bias the upper trapezius which could delay the restoration of balance amongst scapular muscle activation (6).

2. Sitting and standing preferred over prone or supine exercises.

3. Exercises that target impairments in the following order; mobility, motor control, strength and endurance.

4. Longer lever maneuvers in the rehabilitation program.

5. Advance to plyometric based maneuvers.

1kg Shoulder Circuit Example Below:

Progression into dynamic motions may include limited amounts of arm elevation or abduction (approximately 30-45°). Long lever exercises of 90° arm elevation or abduction in the later or last stages of rehabilitation can then be incorporated into the treatment program in the later phases of rehabilitation, but only when the previous maneuvers have been mastered by the patient and has demonstrated little to no symptom exacerbation (6).

Dosage recommendations include beginning with 1 to 2 sets of 5 to 10 repetitions with no external resistance. Additional sets and repetitions can be added based on symptoms and exercise tolerance, with a goal of 5 to 6 sets of 10 repetitions being able to be performed without an increase in symptoms before adding resistance (6).

Resistance may be added next with light free weights of 2 to 3 pounds as a maximum before progressing to elastic resistance.

Feedback is important throughout the rehabilitation phase from clinicians, however, Roche et al., (20215) note that too much feedback can be detrimental to learning as the patient becomes reliant on the knowledge of performance.

References

1. Hickey, D., Solvig, V., Cavalheri, V., Harrold, M., & McKenna, L. (2018). Scapular Dyskinesis Increases the Risk of Future Shoulder Pain by 43% in Asymptomatic Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52; 2: 102–110.

2. Kibler. W. B., Uhl T. L., Maddux. J. W., Brooks P. V., Zeller. B., McMullen. J. (2002). Qualitative clinical evaluation of scapular dysfunction: A Reliability Study. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 11; 6: 550–556.

4. Postacchini, R., Carbone, S. (2013) Scapula dyskinesis: Diagnosis and treatment, OA Musculoskeletal Medicine, 1; 2: 20.

5. Panagiotopoulos, A. C., Crowther, M. (2019) Scapula Dyskinesia, the Forgotten Culprit of Shoulder Pain and How to Rehabilitate, SICOT-J, 5; 29: 1-6.

6. Roche, S. J., Funk, L., Sciascia, A., Kibler, W. B. (2015) Scapula dyskinesis: the surgeon’s perspective, Shoulder and Elbow, 7; 4: 289–297.

7. Sanchez, H. M., Sanchez, E. G. de M. (2018) Scapula Dyskinesis: Biomechanics, Evaluation and Treatment, International Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Journal, 3; 6: 514-520.

8. Sattasuk, W., Sitilertpisan, P.., Joseph, L., Paungmali, A., Pirunsan, U. (2021) A Clinical Evaluation of Scapula Dyskinesis Among Professional Bus Drivers With Unilateral Upper Quadrant Musculoskeletal Pain, Workplace Health and Safety, 69, 10: 460-466.

9. Sciascia, A., Kibler, W. B. (2022) Current Views of Scapular Dyskinesis and its Possible Clinical Relevance, International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 17; 2: 117-130.