Biceps Tendinitis

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 26 Apr, 2023

- •

Primary Biceps Tendinitis

Biceps tendinitis and tendinosis are commonly accompanied by rotator cuff muscle tears or SLAP (superior labrum anterior to posterior) lesions (3). Patients often complain of a deep, throbbing ache in the anterior shoulder. Repetitive overhead motions of the arm initiate or exacerbate the symptoms.

The most common isolated clinical findings in biceps tendinitis is bicipital groove point tenderness whilst the arm is moved to 10 degrees of internal rotation (Figure 1). Pathology of the biceps tendon is most often found in patients 18 to 35 years of age who are involved in sports (3).

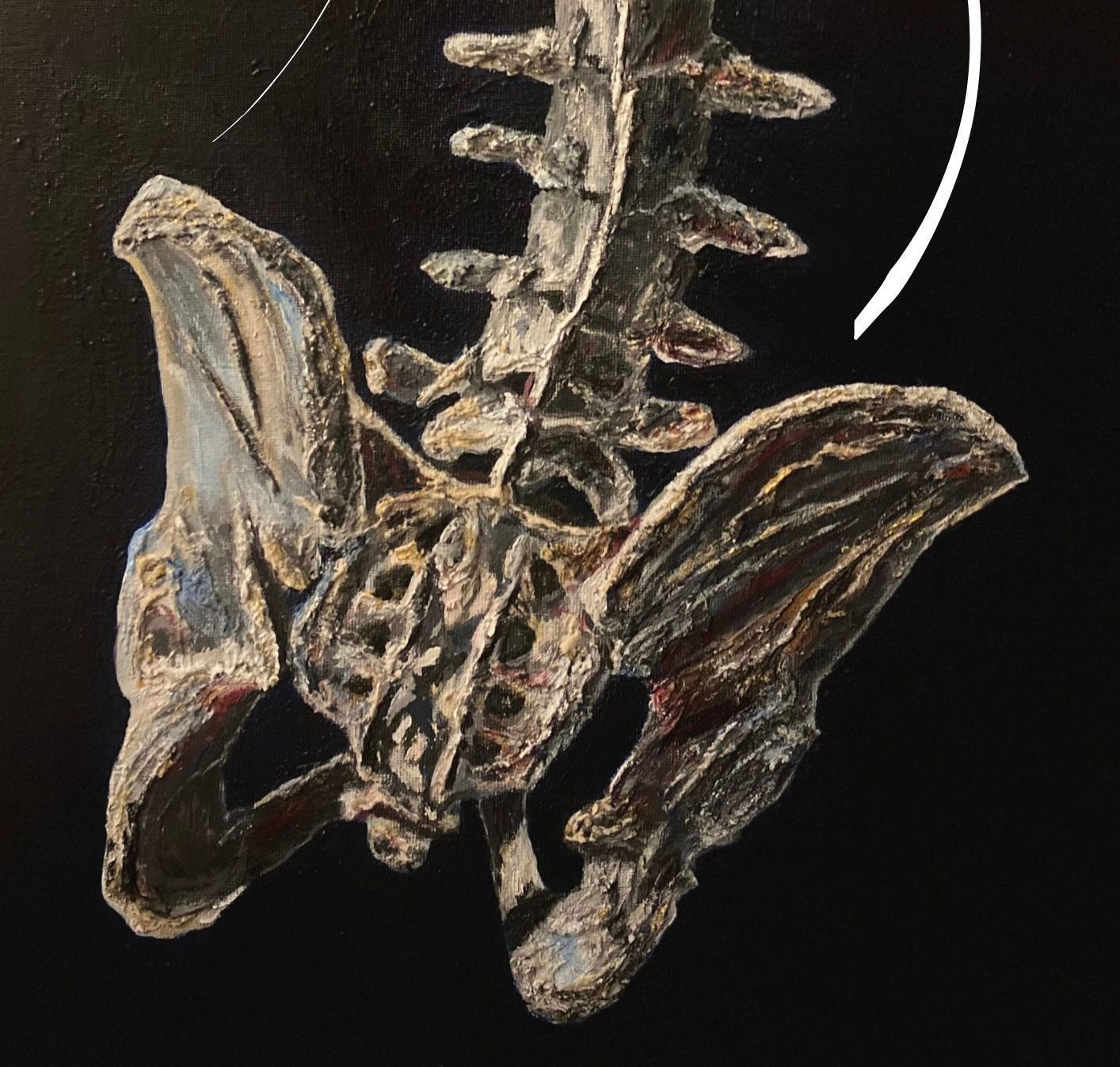

Anatomy

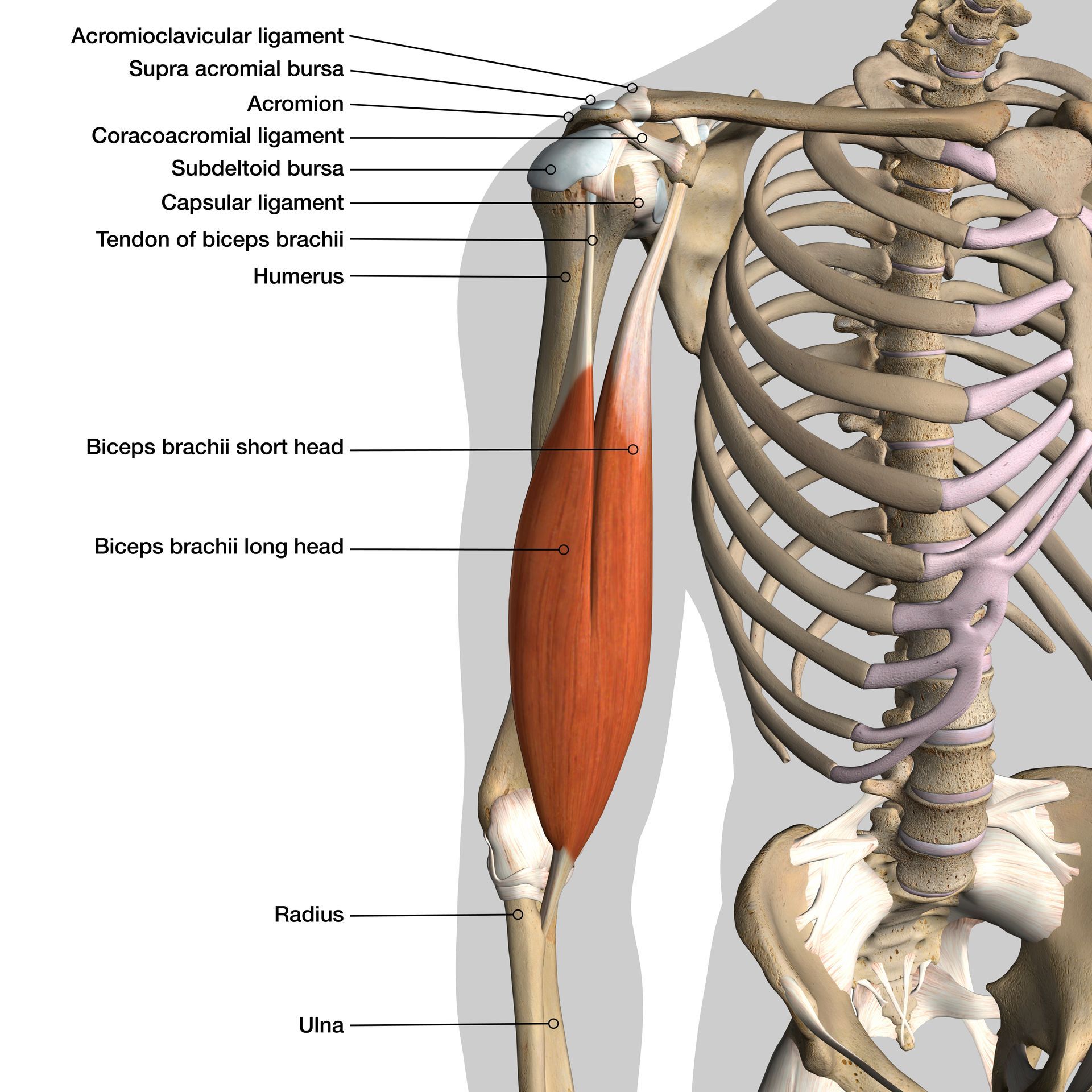

Our shoulder is a ball-and-socket type joint made up of three bones: the upper arm bone (humerus), shoulder bone (scapula), and collar bone (clavicle).

Gross Anatomical Components:

Glenoid The head of our upper arm bone (humerus) fits into the rounded socket in our shoulder bone (scapula). This socket is known as the “glenoid”. The glenoid is covered with a soft cartilage known as the labrum. This cartilage helps the head of the upper arm bone fit into the shoulder socket.

Rotator cuff A collection of muscles and tendons keep our arm centered in the glenoid cavity. These tissues, called the rotator cuff, cover the head of upper arm bone and attach it to the shoulder blade.

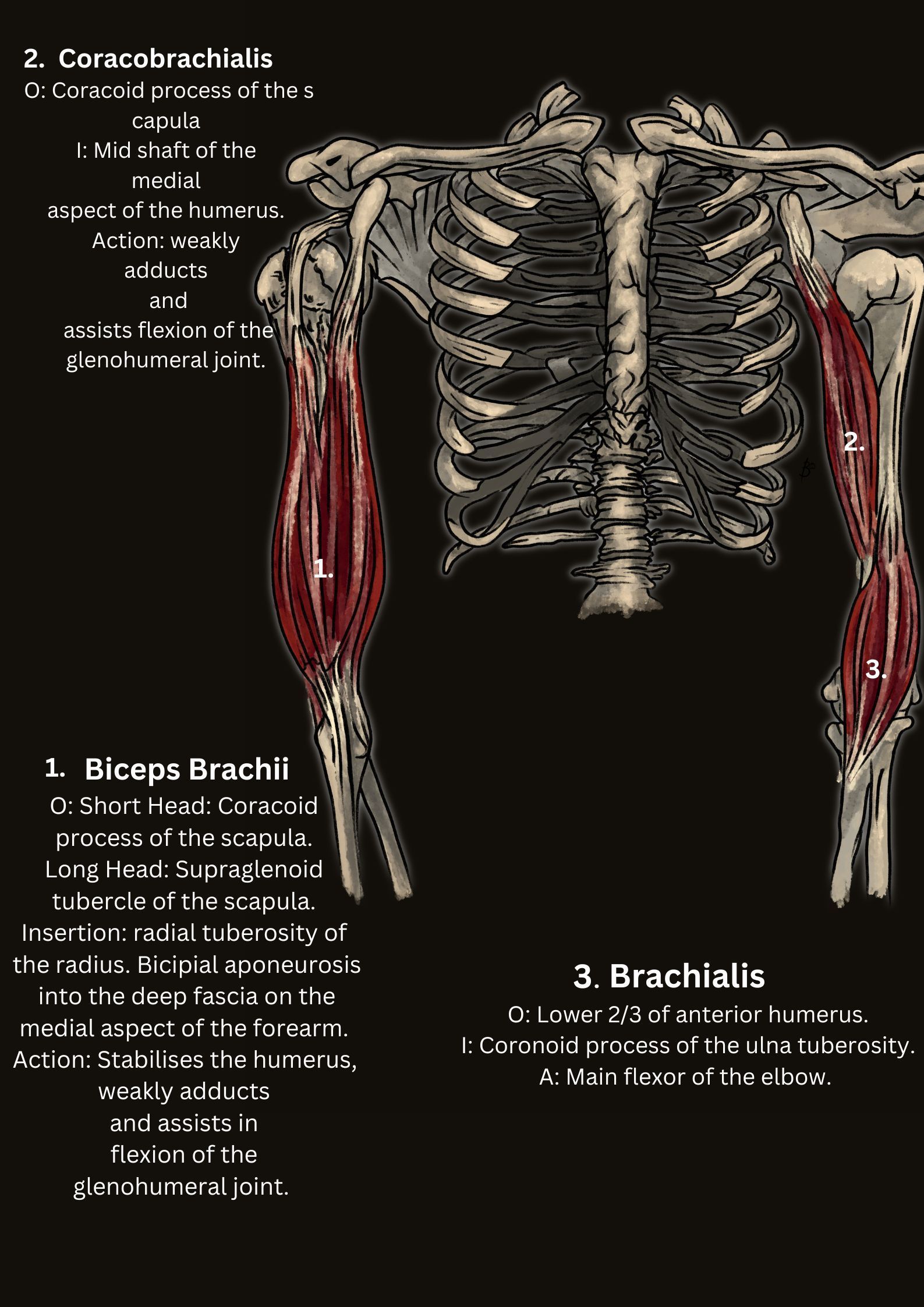

Biceps tendons.The major muscle in front of our upper arm is known as the Bicep muscle which has two tendons that attach it to the shoulder blade bone. The long head of biceps attaches to the top of the shoulder socket (glenoid) and the short head attaches to a process on the shoulder blade called the coracoid process.

Long Head Bicep Tendon The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) originates approximately 50% from the superior glenoid tubercle and the remainder from the superior glenoid labrum (6). The attachment points for the long and short heads of the biceps can be read in figure 2.

Bicipital Groove The bicipital groove is an anatomic landmark that sits between the greater and lesser tuberosities and serves as a critical location of proximal biceps stability. The soft tissue components of the groove create a tendo-ligamentous sling to support the LHB tendon.

Blood Supply The blood supply to the LHB tendon occurs via the anterior humeral circumflex artery. Labral branches from the suprascapular artery may provide blood supply, especially to the proximal portion of the biceps tendon near its origin.Stages of Biceps Tendinitis

In the early stages of biceps tendonitis, the tendon often becomes inflamed and swollen, the tendon sheath can thicken or grow larger as the tendinitis develops. The tendon can become dark red in color in the later stages of the tendinitis due to inflammation (3).

Occasionally, a partial or complete tear of the tendon can occur depending on the injury or damage. A complete tendon tear can result to a deformity of the arm (3).

Biceps tendinitis commonly occurs with other shoulder problems that can accompany the condition:

- Arthritis of the shoulder joint

- Rotator cuff tears

- Tears in the glenoid labrum

- Shoulder instability

- Other diseases that cause inflammation of the shoulder joint lining.

Cause

As we age, most of our daily routine activities can cause wear and tear within the biceps tendon which may result to weakness overtime. Repeating the same shoulder movements over again combined with poor shoulder and upper back posture can be the cause for wear and tear within the joint. Biceps tendinitis can occur from sudden, serious load or strain to the tendon such as lifting a heavy item or performing DIY.

Primary impingement syndrome is considered the most common cause of biceps tendinosis or tenosynovitis (i.e., inflammation of the tendon sheath). This is a mechanical impingement under the coracoacromial arch caused by bone spur formation of the acromion or can occur from thickening of the coracoacromial ligament (3). It may also be caused by osteoarthritic spurs impinging on the bicipital groove (3).

Various jobs and activities can lead to overuse and damage to the biceps tendon. Repetitive overhead motion during certain sports such as swimming, tennis, and baseball can also put people at risk for biceps tendinitis.

Long Head Biceps Tendon (LHBT)

The function of the LHB tendon tends to play a passive stabilising role in the shoulder and it has been proposed that the stability of the LHBT is dependent on the elbow's positioning (figure 2) (9).

Treatment

Physical therapy treatment would involve the practitioner assessing positioning and posture of the neck, shoulders and back and performing clinical tests to understand which specific muscles or joint related compensations might be contributing to maintain a biceps tendonitis.

At the Leagrave Therapy clinic, the practitioner does not prescribe medications, but biceps tendinitis or tendinosis may respond to analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), ice, rest from overhead activity (if perform related activities), or physical therapy.

Shoulder stability and posture related exercises are likely to be prescribed along with specific muscle stretches. The goal of stretching is to regain a balanced range of motion without stiffness or pain in any position. Interestingly, Churgay (2009) believes that a stretching program should include stretching and exercising the hamstrings and lower back as well. A subtle loss of motion in the lower back and hamstrings may lead to a major imbalance of the shoulder-stabilising ligaments and the scapula (Churgay, 2009).

If additional therapy is needed for pain relief, or if the diagnosis is in doubt, an injection of local anesthetic (e.g., 1% lidocaine with or without a mild corticosteroid solution) into the biceps tendon sheath and a referral might be suggested.

Surgery is only considered if conservative measures fail after than three months. Structures causing primary and secondary impingement may be removed, and the biceps tendon repaired if necessary. Debridement or arthroscopic shaving of torn fibers might be performed if less than 50% of the biceps tendon is torn (3). Biceps tenodesis may be considered in serious tears or rupture which involves the attachment of the torn biceps tendon to the bicipital groove or transverse humeral ligament with suture anchors or screws (3). A biceps tenotomy is also a possibility whereby the ruptured biceps tendon is removed from the glenohumeral joint, and tenodesis might be avoided without significant loss of arm function. Tenotomy is the procedure of choice for inactive patients 60 years and older with a ruptured biceps tendon. Tenodesis is a reasonable option for patients younger than 60 years, as well as active patients, athletes, manual laborers, and patients who object to a muscle bulge above the elbow.

References

- Abrams, J. S. (1991) Special shoulder problems in the throwing athlete: pathology, diagnosis, and nonoperative management. Clin Sports Med.; 10 (4): 839–861.

- Ahrens, P. M., Boileau, P. (2007) The long head of biceps and associated tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 89 (8): 1001–1009.

- Churgay, C. A. (2009) ) American Family Physician, 80; 50: 470-476.

- Froimson, A.I. (1975) Keyhole tenodesis of biceps origin at the shoulder Clin Orthop Relat Res; (112): 245–249.

- Iagnocco, A., Filippucci, E., Meenagh, G., et al. (2006) Ultrasound imaging for the rheumatologist. I. Ultrasonography of the shoulder. Clin Exp Rheumatol; 24 (1): 6–11.

- Krupp, R. J., Kevern, M. A., Gaines, M. D., Kotara, S., Singleton, S. B. (2009) Long Head of the Biceps Tendon Pain: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment , Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 39; 2: 55-70.

- Mariani, E. M., Cofield, R. H., Askew, L. J., Li, G. P., Chao, E. Y. (1988) Rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res; (228): 233–239.

- Nho, S. J., Strauss, E. J., Lenart, B. A. et al., (2010) Long Head of the Biceps Tendinopathy: Diagnosis and Management Long Head of the Biceps Tendinopathy: Diagnosis and ManagementJournal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 18: 11.

- Varacallo, M., Mair, S. D. (2021) Proximal Biceps Tendinitis and Tendinopathy, StatPearls; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533002/ [online] last visited 21/11/2021.